Journalism in Action: Beverly Deepe Keever and Her Career

Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-LincolnVietnam

In 1962, when Beverly Deepe Keever arrived in Vietnam as a newly graduated journalism student, there were only eight foreign correspondents in the country. President Kennedy was waging a secret war, insisting the American military “advisors” he was sending to the South Vietnamese government were not participating in combat. However, it was clear to reporters stationed in Vietnam that the increasing American death toll and the ever-growing number of advisors in Vietnam meant America was entering the conflict. Keever was so intrigued by the story that she stayed, only leaving in 1968.

On June 17, 2022, Beverly Keever and Ann Auman recorded a discussion about Beverly’s experience as a journalist during the Vietnam War. Listen to an excerpt on Hawai’i public radio. To hear the full interview, use the link below.

Freelance Journalism

For the first year, Keever worked as a free-lance reporter, submitting stories on speculation to the Associated Press and other newspapers. Her freelance status meant that unlike the eight other resident Western correspondents—all male—she was not tethered to Saigon and she chose to spend much of that time in the countryside. Her freelance status allowed her to report on civilian life, and her gender made her much more approachable to a wider range of informants, including the women in villages. Over her time in Vietnam, Keever wrote several articles about the the war’s effect on Vietnamese women and on civilian Vietnamese attitudes toward Communism and the American presence.

Arriving in Vietnam

When Keever arrived in Saigon on Valentine’s Day 1961, she only had a few suitcases of clothes and her Olivetta typewriter with her. This lightweight typewriter would travel with her across Vietnam throughout the war.

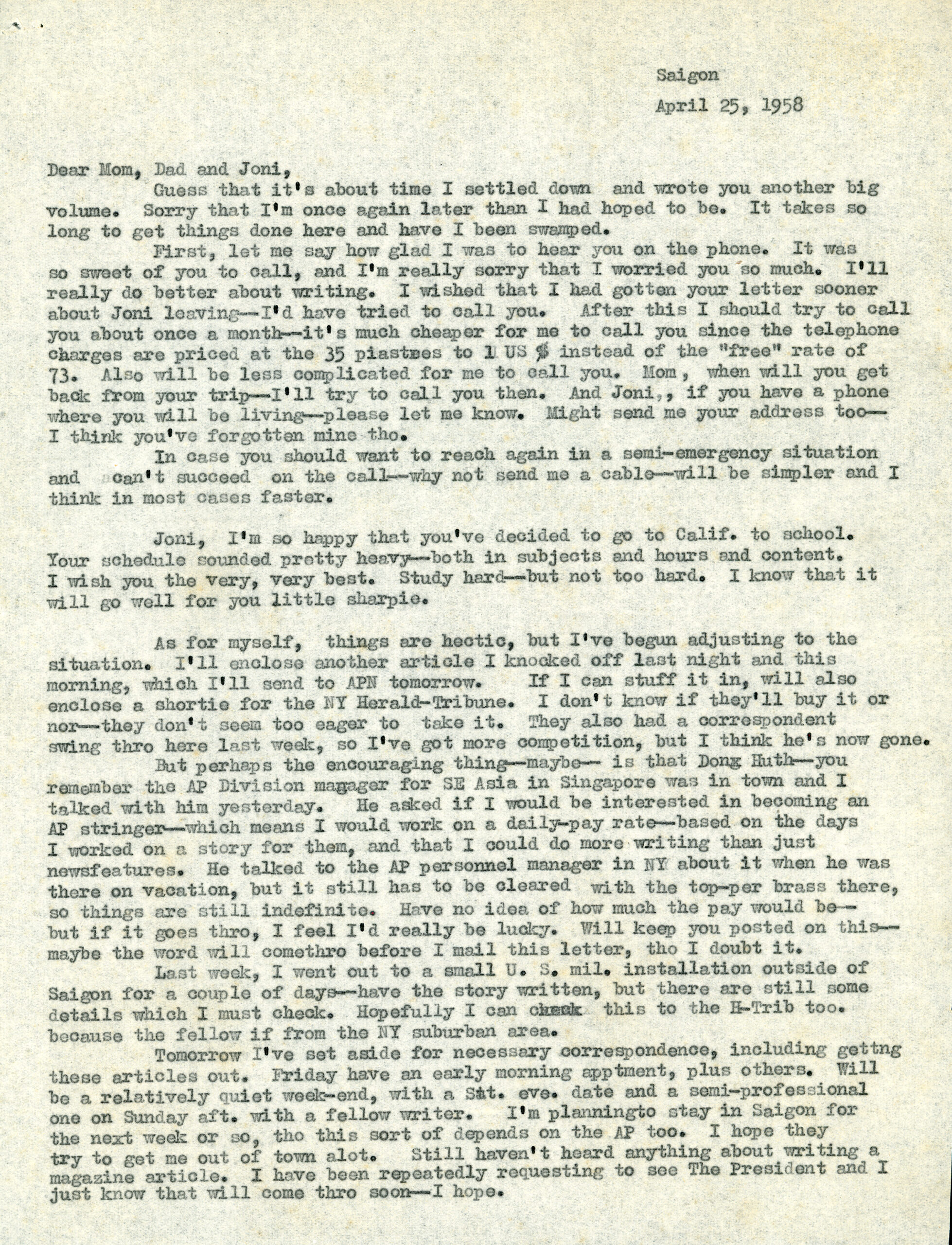

Letter from Keever to her family

This letter from April 1962 discusses Keever’s apartment, her work with the AP, and her new maid. It gives a snapshot into her life in the early months of being in Vietnam.

Writing for the AP

Beverly Keever largely wrote for the AP as a freelancer when she first arrived in Saigon, and any article the AP did not publish she would try to sell on the side to other papers. This photo shows her in the AP office with a Vietnamese member of the staff.

The New York Herald Tribune

In 1964, Keever began writing for the New York Herald Tribune, and she broke several major stories while working there. In 1964, Keever broke the story that North Vietnamese troops had been detected in South Vietnam, although both North Vietnam and the U.S. continued to claim only Viet Cong soldiers were present. After the U.S. elections, however, Washington confirmed the story.

In the same year, Keever revealed the tense relationship between the American and South Vietnamese governments when she published her exclusive interviews with Vietnamese prime minister Nguyễn Khánh. Khánh stated that America’s policy was misguided and that “the United States will lose Southeast Asia.” At the time, Keever was the only American correspondent who was not allowed into the regular U.S. military press briefings, but her articles caught the embassy’s attention and they began to take her work seriously, including letting her into press briefings. While this move may seem like a recognition of her importance as a journalists, it was more likely an attempt to give Keever their side of the story in hopes she would write more favorable press.

Becoming a New York Herald Tribune stringer

After writing for the New York Herald Tribune as a freelancer for several months, Keever finally got hired by the agency around 1964. This 1962 letter from Keever early in her writing for the Tribune asks for clarification around work expectations.

General Nguyễn Khánh

One of the major stories that Keever broke while working for the Tribune was about the tensions between American officials and Nguyễn Khánh in 1964. U.S. officials tried to deny the reports, but the relationship only continued to sour.

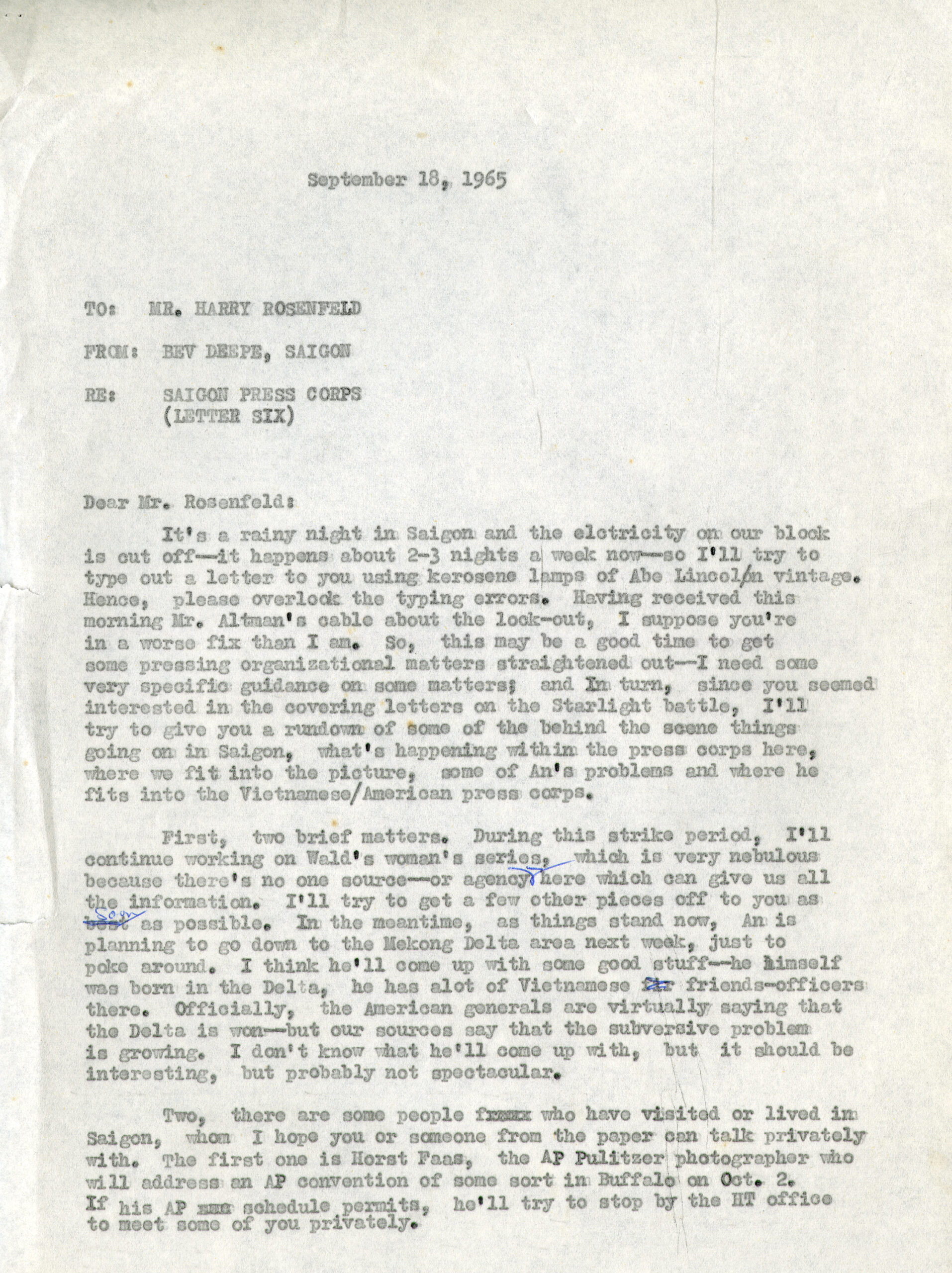

The Saigon Press Corps

In 1965, after years of the American government and military denying journalists’ reports, Keever wrote to her editor explaining her perspective on the situation. In this letter she discusses censorship, surveillance, spies in the press corps, Vietnamese police, Việt Cộng infiltration, staffing, and communication with the main office. The letter gives interesting insight into the daily struggles of Vietnam War correspondents.

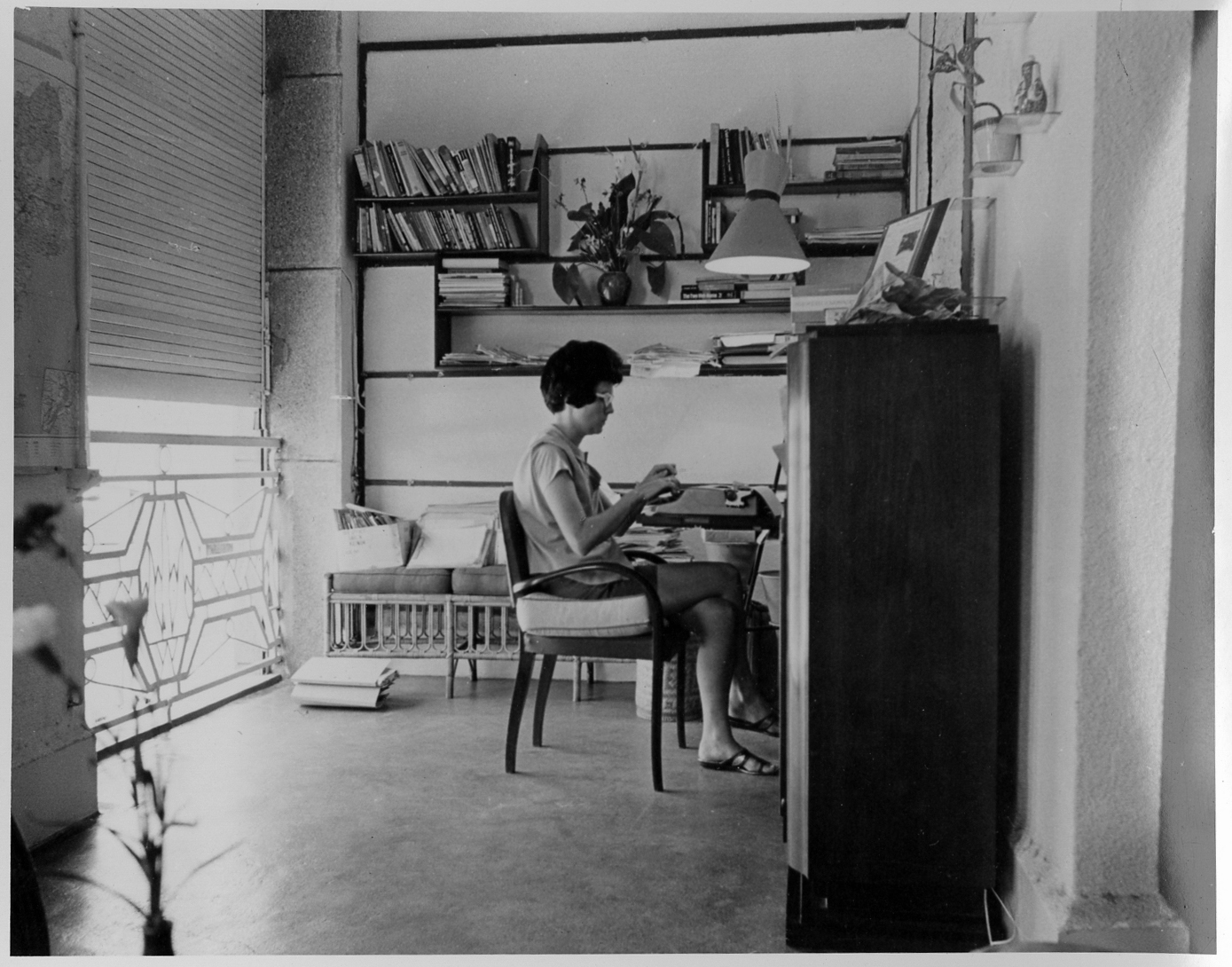

The New York Herald Tribune office

In the early years of working for the paper, Keever’s apartment was used as the Tribune‘s office. In this photo you can see Keever writing at her desk at 101 Cong Ly Rd in Saigon.

North Vietnamese Infiltration

In 1964, Keever broke the story that North Vietnamese troops had infiltrated into South Vietnam, something that both the U.S. and North Vietnamese governments denied. Her reports were ultimately proved to be accurate.

America Officially Enters the War

In 1965 and 1966, two major changes took place. In the political realm, the U.S. officially entered the war following the Tonkin Gulf Incident in 1965. This meant that the number of reporters in Vietnam exploded and the reporters were given increasing access to the U.S. military bases and personnel. Western Press could easily become Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) accredited journalist, which would allow correspondents into official press briefings, entitle them to free military transport, and insure cooperation from military officials in the field. With a press card, reporters could go almost anywhere and talk to almost anyone without U.S. military interference. If the journalist wrote an unfavorable story, the press cards could be revoked, but this was rare. Keever began covering more military stories during this time.

The second change came in 1966, when the New York Herald Tribune staff in New York started a strike that ultimately closed the paper permanently. During the strike and after the paper’s closure, Keever wrote for many papers in the U.S., U.K., and Australia, at the same time as she was trying to get another secure job.

Tonkin Gulf Incident

In 1964, Saigon began to receive reports that North Vietnamese ships had fired on a U.S. Navy ship in the Gulf of Tonkin. This news sent shockwaves through Saigon’s politics and ultimately led to America officially entering the Vietnam War. In this article, Keever writes about the somber mood in Saigon.

Navy 7th Fleet

Shortly after the Tonkin Gulf Incident in 1965, Keever went to the Gulf of Tonkin on a 7th Fleet Navy Vessel. She took many photos of the aircraft carriers and wrote several articles about the Fleet.

The New York Herald Tribune closes

After continuous strikes, the already financially precarious New York Herald Tribune closed. Keever had not been able to publish anything in the paper for months during the strikes, so the closure was not a surprise. Keever was freelance, writing for many American, British, and Australian papers during this time.

New York Herald Tribune staff

At the time the Saigon office closed, there were several staff who were layed off. This photo shows Keever on the far right and Phạm Xuân Ẩn on the far left. Keever had already worked with Ẩn for several years, but he successfully hid that he was a communist spy. Keever went on to the Christian Science Monitor, while Ẩn wrote for TIME.

The Christian Science Monitor

Eventually, Keever landed a job with The Christian Science Monitor. While working for the Monitor, she was one of the first reporters to suggest America might lose that war in response to the Tet offensive in 1968.

In 1969 she was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize in international reporting by the Christian Science Monitor for her earlier coverage of the Khe Sanh combat base while it was being bombarded by communist artillery. “Most of Beverly Deepe’s readers presume she is a man—for her beat in Vietnam is rough, tough and dangerous,” the Monitor’s nomination letter read, “Yet Miss Beverly Ann Deepe, who hails from little Carleton, Nebraska, has been reporting the war and political developments from Saigon and military outposts such as Khe Sanh for seven years now. She holds her own with hosts of masculine correspondents—and asks no favors.”

In 1968 when she left Vietnam, Keever was the longest serving Western news correspondent of the war.

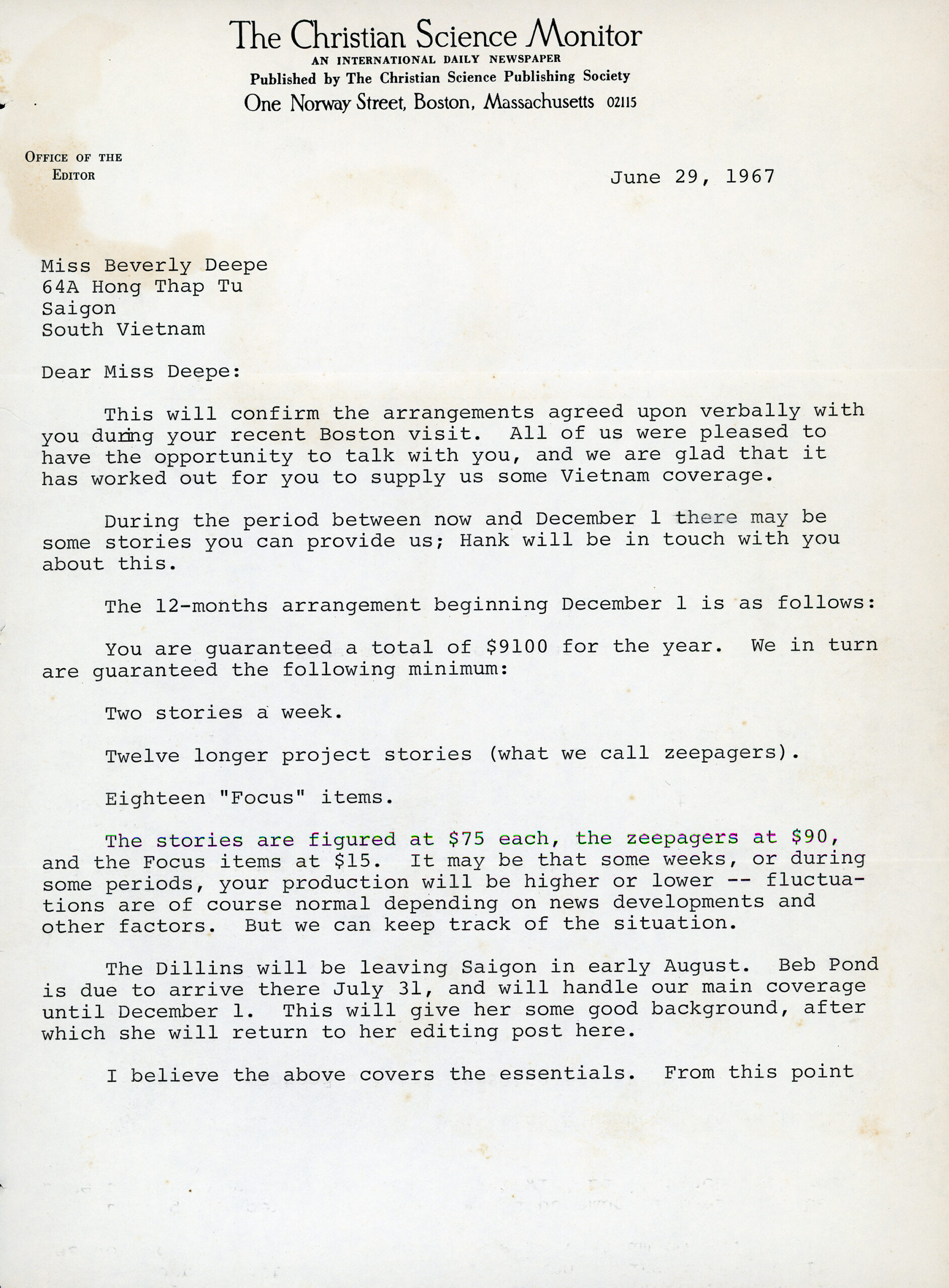

Becoming a Salaried Employee

This letter from 1967 lays out Keever’s employment contract at the Christian Science Monitor. She was thrilled that she was guaranteed $9100 per year, since it meant no matter how many of her articles the Monitor decided not to publish, she would still get paid.

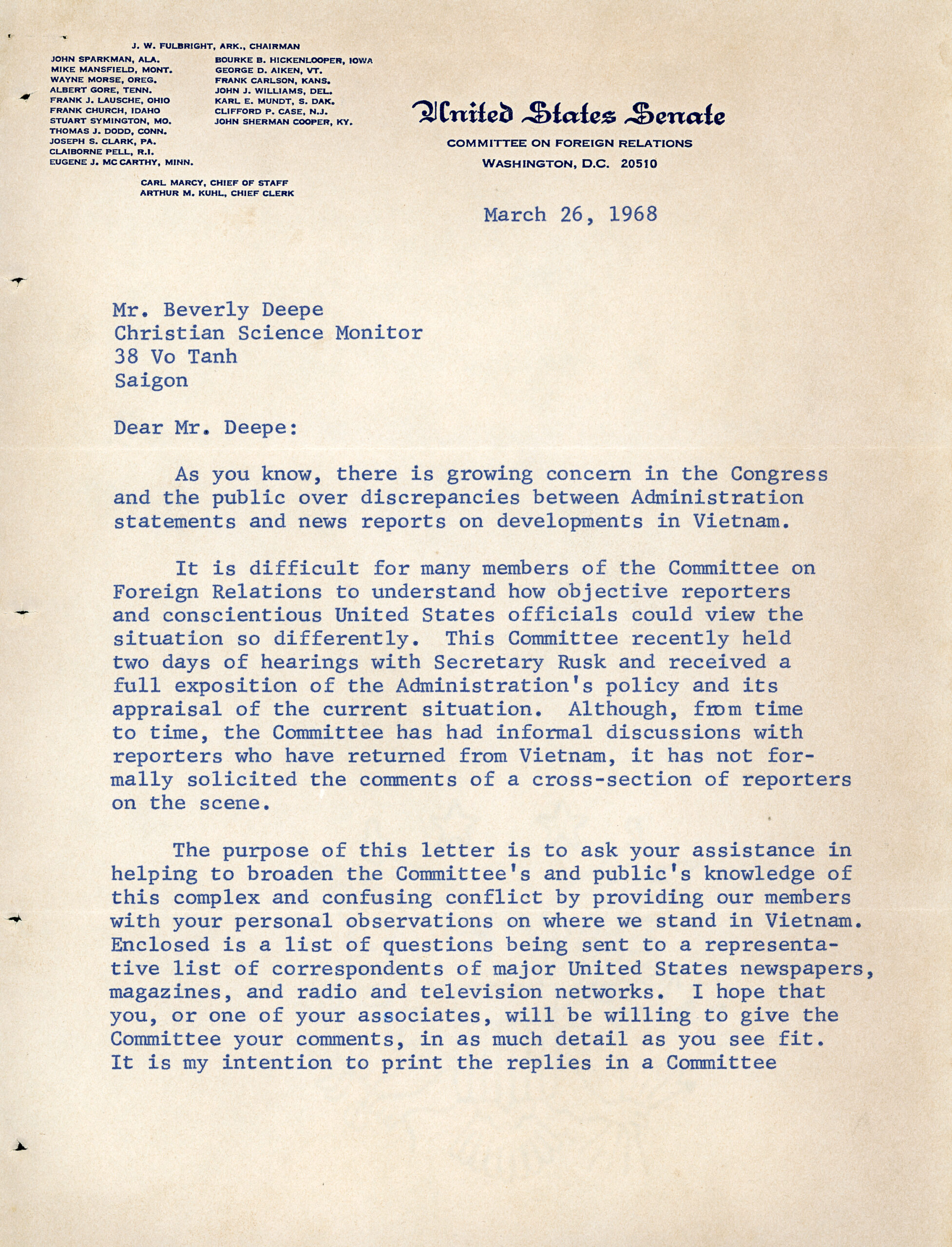

Uncertainty in U.S. Politics

While the 1968 Tet Offensive broke Americans’ confidence in the military’s ability to win the war, trouble had been brewing for years. Official government reports on Vietnam were often wildly different from what reporters saw on the ground, leading to confusion, governemnt denials, and animosity between the two sides. This letter from the U.S. Senate tried to get to the bottom of the problem, asking Keever what was actually happening in Vietnam.

Writing About the Battle of Khe Sanh

This article was the first in a series Keever wrote on the Battle of Khe Sanh. The series eventually won Keever a Pulitzer Prize nomination in 1969.

Previous section: Travels through Asia

Next section: Return to America