Journalism in Action: Beverly Deepe Keever and Her Career

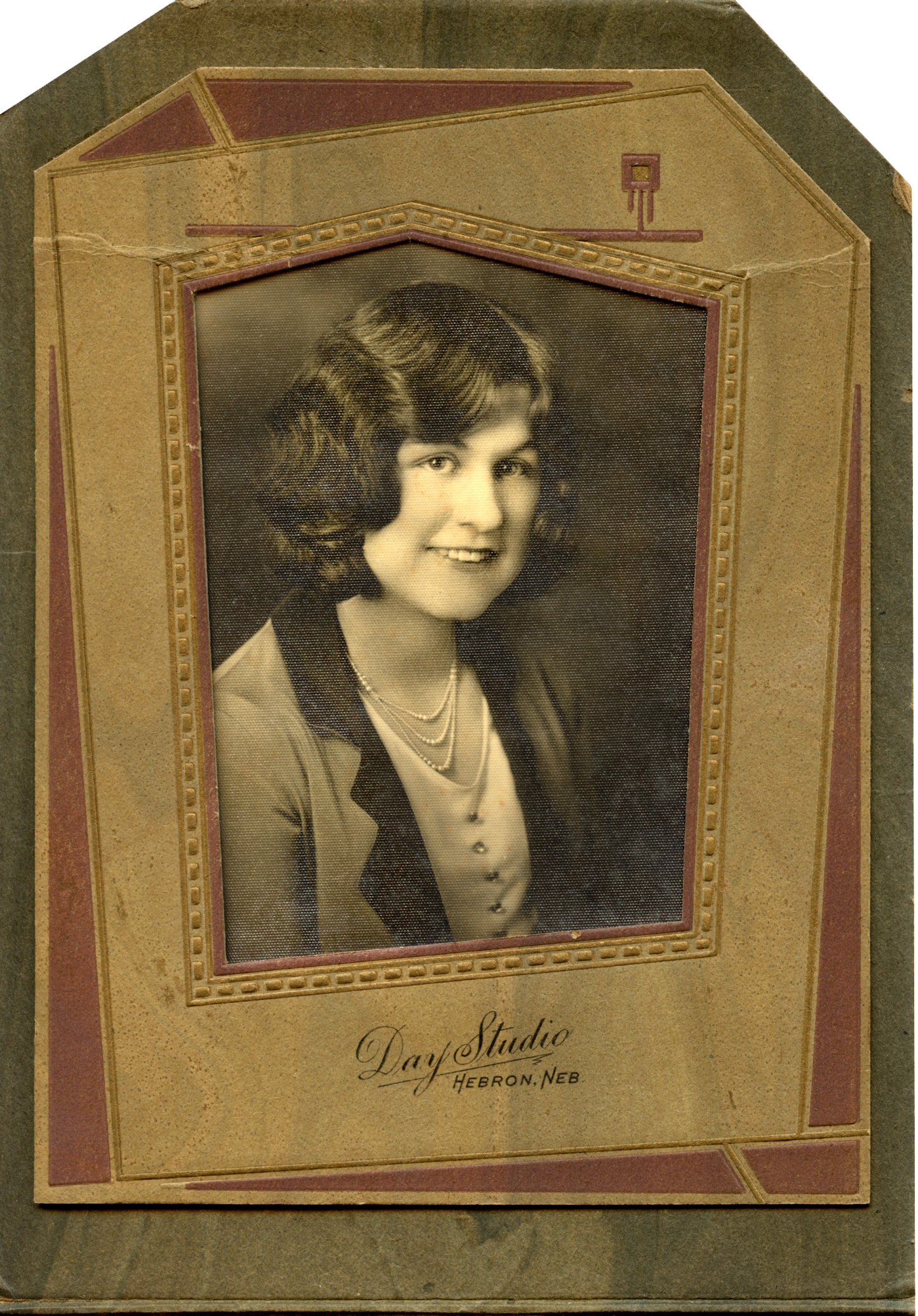

Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln“The Making of a Lipsticked Correspondent”

Beverly Deepe Keever

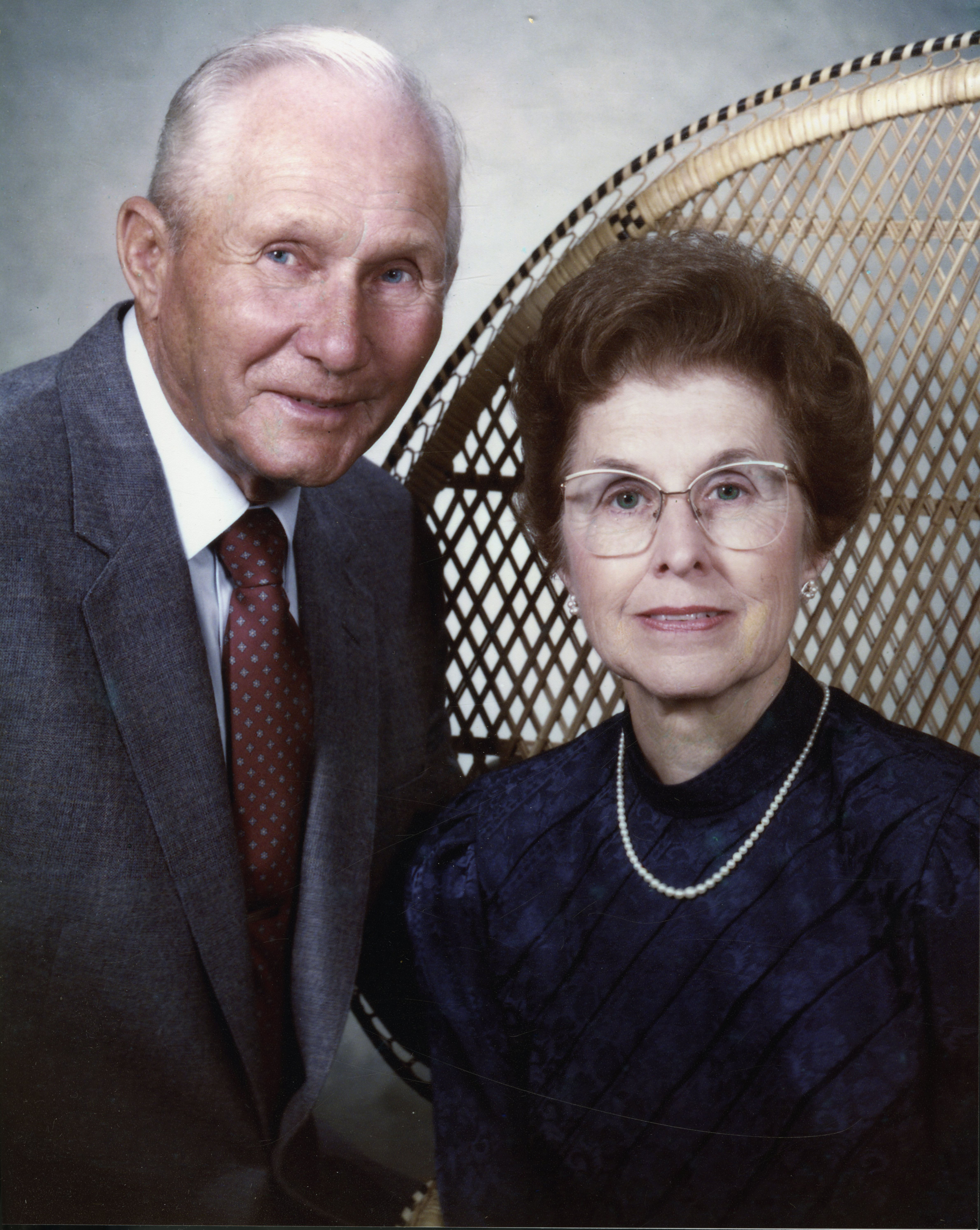

Martin and Doris Deepe struggled through–even personified–Nebraska’s family farm revolution for 69 years. It’s not exactly a life they envisioned upon graduating from high school. Nor did they even want that kind of future. Martin wanted to be a veterinarian; he loved animals, especially horses. Doris wanted a college education; she loved to research. But the Depression and Dust Bowl days pulverized their separate dreams.

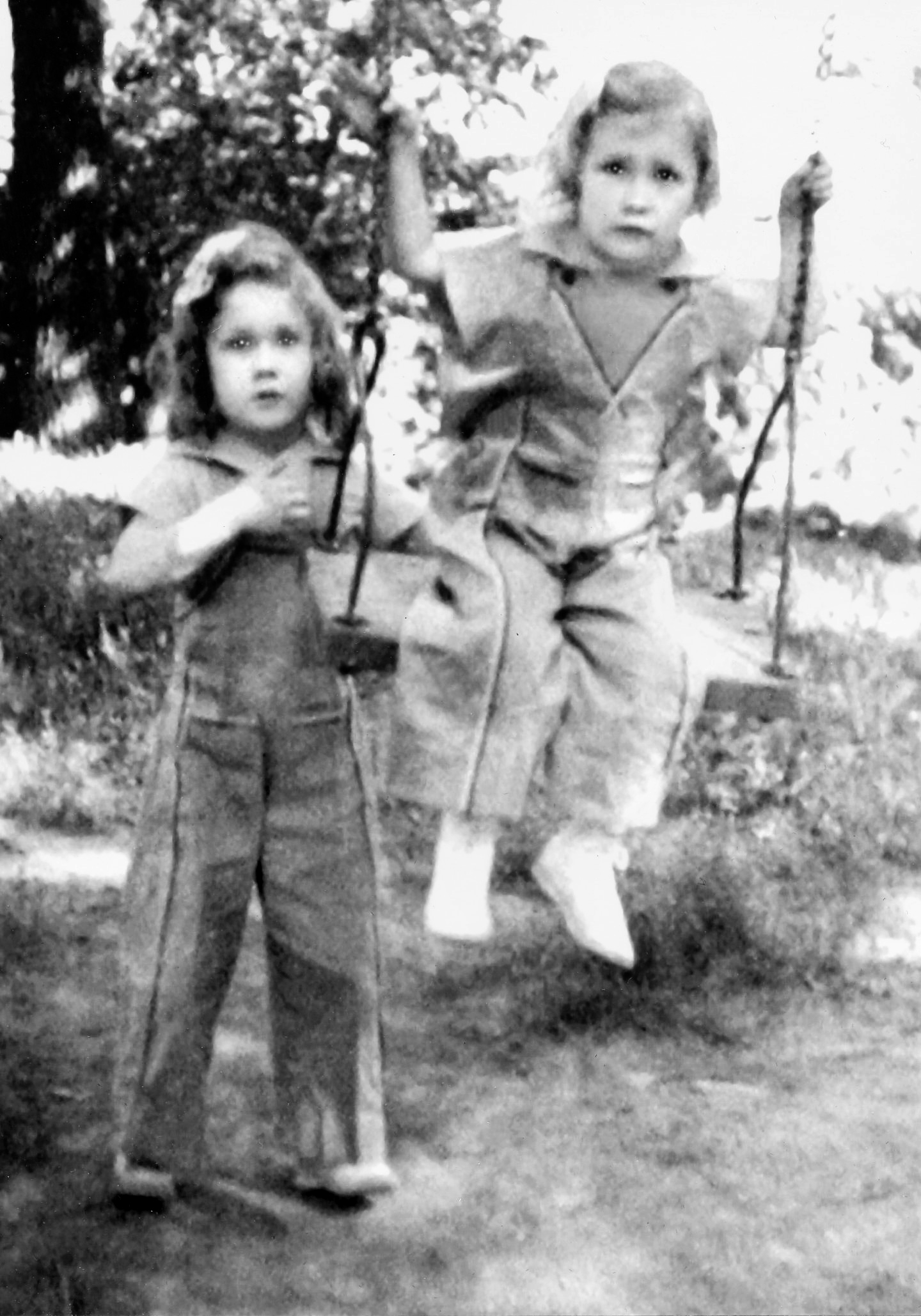

In 1934, amidst the driest year on record, they were married in Kansas, having eloped across the border as did many young couples without funds for a wedding. A year later, they had their first daughter, Beverly Ann, and two years later came a second daughter, Barbara Joan, usually called Joan. The young couple yearned that their two little girls would have the advanced education denied to them.

Then, 50 years later, having lived through a lot of Nebraska’s farm revolution, the couple celebrated their wedding anniversary in a World War II Quonset hut that served as the community center in Belvidere, six miles from the county seat of Hebron in the geographic center of the country and near the rough ruts of the Oregon Trail.

But two years later, Martin suffered a fall that shattered his leg and required two surgeries; he continued to farm but walked in pain and later leased his farm land. Farming, one of the nation’s most dangerous occupations, had taken its toll. So, in 2003, 69 years after they began farming, Martin and Doris decided to sell their farm equipment and household items not already moved in 1996 to their new home in Hebron.

The farm equipment auction telescoped Nebraska’s farm revolution made during the couple’s 69 years. The last thing to be auctioned off was Martin and Doris’s equipment used when they were first married and farmed with horses, including horse-drawn two-bottom and three-bottom plows.) The sale bill casually listed these as “other older items for iron.”

In contrast, when Martin finished farming, he was using what he called his “big John Deere” (a 1990 John Deere 4456 tractor with powershift that he had used for 2,015 hours) and his “little John Deere” (a 1963 John Deere 3010 tractor using a single hydraulic standard shift). But he also held onto his first Farmall that he still used for cutting roadside weeds.

Martin once explained Nebraska’s quiet revolution to a dozen young journalists from mainland China, where a bloody revolution 40 year earlier had created the world’s most populous communist country and a U.S. enemy. (No one seemed aware of the bloody revolution in the Great Plains decades earlier when Native Americans were driven from their homeland.) The English-speaking Chinese were making fast notes and checking their tape recorders so that they could write a feature story for the University of Hawaii journalism class that Bev was teaching in 1988. They were also learning first-hand about what Bev had told them was an endangered species—the American family farmer—and the modernization of U.S. agriculture that had precipitated the decline.

Martin told the journalists that the revolutionary factor for his farming was a change of power. “In our childhood years and when I started farming, horses provided power for our equipment. I used horses for 10 years after we were married and then I got a gas Farmall tractor. That really revolutionized my farming because it was all-purpose; I didn’t need horses for planting, weeding or harvesting.”

The tractor also pulled a binder, which was used to cut oats or wheat and tie a string around them into an armload of straw and grain. Bev often helped gather an armload of bundles and piled them in a teepee-like stack so that the rain would run off them. When dry, a community of neighboring farmers helped to pitch these bundles into the small threshing machine that Martin operated with his tractor furnishing the power to separate the grain from the straw. When finished, the men moved onto the place of the next farmer and furnished help for him.

At noontime, Doris cooked a hearty meal for the half dozen men helping at the Deepe farm. “We had no electricity,” Doris told the Chinese journalists, “and so no refrigeration. We had to run into town to get the meat, and usually I also served mashed potatoes and gravy, vegetables and pie.” The food was so delicious that the helping hands loved to eat at Doris’s table.

When everyone’s grain was threshed, they would come to the Deepe house for socializing. “We made homemade ice cream with ice bought in town, and the men would settle up their bills and pay each other,” Doris recalled. “It was a fun evening with neighbors and friends and everyone was so glad when the threshing was over because it was always so hot!”

From the 1950s on the tractors got bigger, better, faster. Martin’s binder and threshing machine were replaced by his combine that was pulled by the tractor but cut the oats or wheat and separated the grain from the straw. The combine stored the grain in a bin on the top of the machine and spewed the straw out the back in a big puff. When the bin was full of grain, it was dumped into a trailer that Doris pulled behind their car and joined a long line of trucks at the elevator in their small neighboring towns. Bev and Joan rode along, hanging onto their seat over the bumpy dirt road. By the 1970s the tractor-pulled combine, in turn, was rendered obsolete by a self-propelled one with its own motor so Martin didn’t need to use his own tractor anymore.

His first Farmall tractor was equipped with headlights, so Martin often worked from morning on into the cool night. By the 60s, he said, tractors added cabs, which he had on his big John Deere and these cabs could be air conditioned and equipped with a radio and even television. “The cab kept me out of the weather, during hot or cold spells,” he added. Then he also began using chemical fertilizer, herbicides, and insecticides. He was perpetually busy. Sister-in-law Audrey Else recalls Martin saying, “If you see nothing to do on the farm, you aren’t looking around.”

The revolution Martin was living out on the farmland did not soon trickle to the farmhouse and Doris’s domain. “My work was hard and the same as my mother and grandmother,” Doris told the journalists. The first-married couple lived on what Doris routinely called “the nob,” a “place unfit to live in” because single-lumber sides of the house lacked insulation. Doris recalled even 80 years later the Dust Bowl days when, without much luck, she jammed wet rags around the window sills to keep the fine, black dirt from entering the house. One day she had laundered Joan’s blue snow suit, hung it on the clothesline to dry but before she could snatch it a wind had blackened it with so much dust she could hardly wash it all out.

“The nob” was isolated, sitting dozens of miles on dirt roads from the nearest town and half a mile from the nearest neighbor. It was situated on a quarter section of land (160 acres) belonging to Martin’s father, but it was heavily mortgaged and during the depression barely enough crops were raised to pay for the mortgage and taxes.

Water for the house had to be carried from an outdoor well in a bucket and in the winter, the water froze in the bucket. It was hot in the summer, made worse because Doris cooked on a stove that burned coal, wood or corn cobs. Besides house work, Doris also raised vegetables in a nearby garden; Bev and Joan planted zinnias and cosmos too and helped pull weeds and shell peas. Doris also raised chicks in a brooder house that later provided meat or eggs from hens in nests that often pecked at Bev or Joan as they sought to gather the eggs. One year Doris raised turkeys to earn extra money. She had to carry corn and water down a hill to them; Bev and Joan helped by pulling a tall pail of water in their toy wagon. But she lost money because a freezing rain damaged the fowl before they could be sold. Decades later, she still doesn’t like turkeys, not even eating any at Thanksgiving.

Joan learned to milk the cows, but insisted on feeding the cats first by squirting milk from the cow’s udders directly into their nearby pan. Bev escaped these duties in the barn because the dust from them provoked her allergies that continue to this day.

What Doris called “the nob” proved to be a giant playground for Bev and Joan. They played with baby chicks, kittens and a black-and-white mutt named Tippy. As the puppy grew, he became naughty, ripping the leg of Joan’s green play suit and later chewing up the hemline of Doris’s go-to-town dress that was being aired on the clothesline. He mysteriously disappeared but later was replaced by Ole’ Shep, a pure German shepherd dog adept at rounding up cows.

The girls also played with Patsy, a black-and-white Shetland pony that Martin transported to the farm in a car with the pony’s head drooping out a window. He bought the pony so that Bev could ride it five miles to country school. But the pony was too spunky to get Bev to school on time, so Martin had to drive the girls to Coon Ridge but they walked home during decent weather, stopping to pick roadside dandelions and other wild flowers to hand to their Mother when they reached home, where they in turn were greeted with cookies.

In the school that Martin had attended a generation before her, Bev received her first eight years of education. There she became fascinated with the book The Good Earth, Pearl Buck’s vivid description of life and culture on mainland China, and she was smitten with the dream of visiting that country and others in the region. For one summer Bev worked in the Deshler Broom Factory—then the world’s largest but now shuttered. It was such hot, dusty work that Bev vowed then to study hard so as to avoid such onerous future jobs.

In high school Bev wrote an essay on soil conservation in a county-wide contest. She used research gleaned from pamphlets she and her father, Martin, gathered from a county office. She won first prize and that helped her to envision a career in journalism. Upon graduation, she attended the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, having received the Regents Scholarship and support from her parents. She was selected for Phi Beta Kappa, honoring high scholarship, and for Mortar Board for campus leadership. She then attended the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism in New York City, where she was awarded a scholarship and graduated with honors. Working in New York for two years, she built up a nest egg that enabled her to pursue her childhood dream by visiting Asia, where in 1962 she began covering the Vietnam War.

In 1953 the family farm revolution came to Doris’s world. Then she and Martin bought a farm blessed with rural electrification that could turn night into day. The farm land of 160 acres also held a house, several barns, a garage, chicken house and outhouse. That farm, adroitly managed by the couple, their hard work, penny-pinching and good fortune made possible the advanced education they wanted for their daughters.

Parts of the farm house were historic, dating back to the 1890s. “I thought it was heaven,” Doris often exclaimed. The house was wired for electricity with ceiling lights replacing the kerosene or gas lamps used earlier. For the first time in 19 years the family rejoiced with an indoor, flush toilet and bathtub, and a washer and dryer that freed Doris from hanging clothes on an outdoor clothesline during winter days that nearly froze her fingers. An electric stove replaced that wood-and-cob-burning cook stove she was used to; an electric refrigerator replaced the ice box that cooled foods with chunks of ice bought in town but soon melted away, leaving water to drip into a pan beneath it. Electric and gas furnaces replaced a pot-belled heating stove and also cooled the house in the summer. An electric pump brought water into the house from a well instead of being hand-carried in a bucket or pumped by hand. “Electricity transformed my life,” she told the Chinese journalists. “Before that my hard work was the same as that for my mother and grandmother.”

After electricity, came the telephone. At first in 1953, the family was on a party line, allowing others to listen in. Then in the 1980s a private telephone was installed, when only the family’s phone would ring. But long-distance calls to Bev or Joan were so expensive that Martin would point at his wrist watch to alert the talkers that their time was up. Later Doris bought a cell phone saying, “That’s nice because I can carry it into the yard with me.”

Besides housework, cooking and gardening, Doris also began to help in the fields when the couple found they could irrigate a more profitable crop of corn by using siphon tubes. In the flat land of the farm they purchased in 1953, they switched from raising the sorghum milo on dry land to corn that could be watered from a ditch running along the corn rows.

But the watering was back-breaking. For each row of corn, Doris had to kneel on her knees along the top of the ditch, then jostle a U-shaped metal tube to fill it with icy water supplied by a motorized pump, cap one end of the tube with her finger while lifting the other end across the ditch to start the water flowing down each row of corn. Neighboring farmer Kelly Dowdy recalled when she visited the couple late one evening after their long watering work-out, they were resting on their outdoor picnic bench; the legs of their trousers and boots were caked with mud and their fingers were still warming up from the cold water.

By the 1970s, the couple’s siphon tubes became obsolete and were sold as antique pieces of junk on their farm equipment auction. By then, the couple was one of the first in the area to install an Electogator, a central pivot that circles the field on wheels like a giant metallic caterpillar while spewing a stream of water on the crop below. The couple had visited a demonstration of the invention that for the first time gave a farmer control of rainfall without depending on Mother Nature. “That was a miracle-invention,” Doris exclaimed, remembering her experiences during the Dust Bowl days. “We need one of those.” They installed one on a half-section of land they had purchased in the 1960s and later added one on their quarter-section near their farmhouse. Those two miracle-inventions still circle their two farms when no rain falls from the sky.

Electrogators are still manufactured and home-based in Deshler, only miles from where Beverly had years earlier worked in the world’s largest broom factory. Today Electrogators are manufactured also in Kansas and Beijing, with offices in Russia, Argentina, and Mexico.

In 2005, Martin died, at age 94. Doris traveled with her daughters to the Grand Canyon, New England for autumn leaf-peeping and San Francisco, where Joan founded and operated her own secretarial service in the financial district. Joan’s fingers that typed during the day were busy in the evening doing fancy needlework, including embroidering samplers and quilts for her Mother and Bev.

On March 7, 2015, Doris celebrated her 100th birthday. At her celebration with family, she scanned the front page of the New York Times published on the day she was born. That newspaper told of international turmoil, including fighting at sea between Russia and Turks in the Ottoman Empire. She and Audrey Else–her younger sister and only other surviving sibling of nine children—reminisced over a black-and-white snapshot of the entire Widler family taken before four brothers and another sister were in uniform during World War II.

Doris was born two years before President Woodrow Wilson dispatched American doughboys to fight in World War I in Europe and before a revolution overthrew the Tsar of Russia, paving the way for a communist country. Her next decade saw the advent of television and a talking movie. The so-called Jazz Age, when Doris danced the charleston, ended in 1929 with the stock market crash that led to the Great Depression of the 1930s in the United States, while in Europe Adolph Hitler began his rise to power that led to World War II. Then erupted the atomic age and in 1949 the communist takeover of mainland China. A year later came the Korean War and the dawn of the computer age.

During her 100-plus years, Doris had struggled through Nebraska’s family farm revolution and experienced great swatches of 20th century history and conflict, including two world wars and numerous smaller ones. One of those smaller wars in Vietnam was covered in the 1960s by her daughter Bev. Doris died in 2020 at the age of 105.

All photos courtesy of Beverly Deepe Keever

Previous section: Youth