Thich Quang Duc- The Burning Monk

On June 11, 1963, an American journalist named Malcolm Browne captured possibly one of the most influential photographs ever taken. The photo depicted a Buddhist monk sitting cross-legged in the middle of a Saigon intersection engulfed by flames. When he saw the photo, United States President John F. Kennedy observed, “No news picture in history has generated so much emotion around the world as that one” (Keever, 100). Before 1963, few people in the United States knew much about Vietnam and its impending civil war. Who was the monk in the photo? Why did he set himself on fire? What was the impact of his action? These were questions that many people around the world asked themselves when they saw this picture that remained in their memories.

During the early 1960’s, Ngo Dinh Diem, a Roman Catholic puppet politician put in place by the United States, controlled South Vietnam (Keever Collection, Packet 128). Under President Diem, Buddhists, who made up the majority of the population were persecuted and almost the entire South Vietnamese government was Roman Catholic. Buddhists were subjected to persecution. This included not being allowed to celebrate religious holy days, being forced to convert in order to gain upper status in the military and heavy taxes on Buddhist monasteries (Keever, 93) Catholics controlled the military and received tax exemptions (Keever Collection, Packet 7). President Diem even dedicated the country to the Virgin Mary in 1959. Buddhist leaders sought equality for themselves. They released a list of five demands to the Diem government to make this equality possible. The list of the demands is as follows:

- Lift its ban on flying the traditional Buddhist flag;

- Grant Buddhism the same rights as Catholicism;

- Stop detaining Buddhists;

- Give Buddhist monks and nuns the right to practice and spread their religion; and

- Pay fair compensations to the victim’s families and punish those responsible for their deaths.

(Keever, 94)

Diem ignored the demands, and this led the Buddhists to take action. Buddhist leaders believed that if at least one of them carried out an extreme protest such as self-immolation, their demands would gain the attention they believed they deserved. One of the leading monks, Thich Quang Duc, volunteered to set himself on fire to gain the world’s attention to the atrocities that were occurring in South Vietnam.

Just three days before his self-immolation, Beverly Deepe Keever, interviewed Duc and asked him what was going through his mind and why he was doing this (Keever, 98). Duc, a Mahayana Buddhist and somewhat radical, felt confident that his choice would ensure the Buddhists would not be overlooked in the future. He believed that by giving up his life, future generations would have the freedom to practice Buddhism free of government oppression (Keever Collection, Packet 128).

In the evening of June 10, 1963, local Buddhist officials contacted several correspondents of Western newspapers and told them to be prepared for a major story that would develop the following morning. Only one correspondent heeded their advice, Malcolm Browne. At about 9:20 a.m. on June 11, Browne witnessed Duc’s self-immolation, photographed it, and sent it back to the United States to be published as quickly as possible. Browne was the only correspondent with a camera that fateful morning. The next morning Americans saw the photo in a variety of different newspapers, though some, such as the New York Times, chose not to print it believing it was too graphic of a photo to be released to the public.

The photo of Duc became one of the most influential in human history. Several others, including several Buddhists, followed Duc’s example and committed violent suicides to get a religious or political message heard, many occurring during and for the Vietnam War. The photographer, Malcolm Browne, won the Pulitzer Prize in international reporting for that year. Some historians attribute the eventual fall of the Diem regime, which happened later that year, in part to Browne’s photo and the amount of attention it brought to the subject (Keever, 100). Thich Quang Duc sacrifice remained historic and Bev Keever played a small role in his last few days. Keever talks about her interview with Duc in her book, Death Zones and Darling Spies and also has information about the events of 1963 in her collection now located in the Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries.

For more information on Malcolm Browne’s photograph, please visit https://www.ap.org/explore/the-burning-monk/

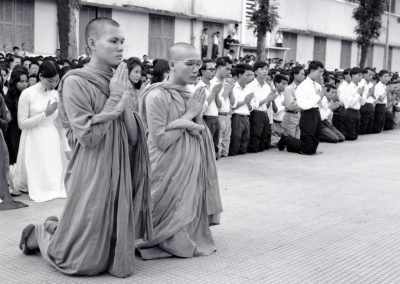

Buddhists at Pagoda (363-0760)

“Buddhist — Monks at Pagoda — Aug 20-1964” “A row of soldiers keep a large crowd of people from coming through the fence into a plaza. In the center of the photograph, a soldier and a civilian carry an injured man. Another man takes a picture.”